Let's Stop Pretending Corporate Comms Can Be Authentic

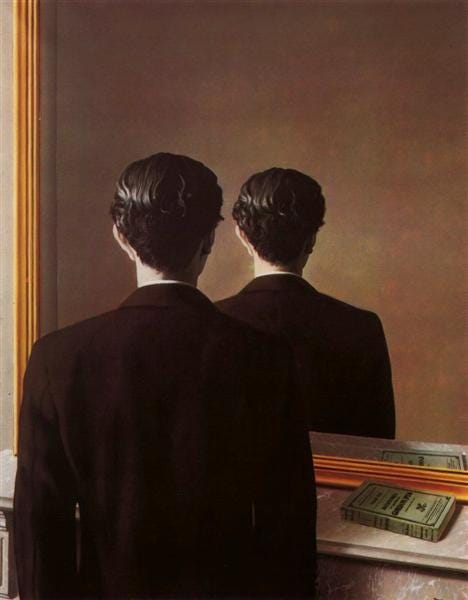

The harder we perform authenticity, the more inauthentic we become

Authenticity in corporate comms never existed in the first place

When ChatGPT burst onto the scene a couple of years ago many comms pros didn’t panic. The writing the tool generated was clumsy, anodyne, often laughable. It’s a decent first draft, they shrugged, but you still need experienced comms pros to fill …